- Home

- Christina Collins

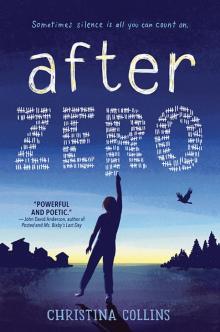

After Zero

After Zero Read online

Thank you for downloading this Sourcebooks eBook!

You are just one click away from…

• Being the first to hear about author happenings

• VIP deals and steals

• Exclusive giveaways

• Free bonus content

• Early access to interactive activities

• Sneak peeks at our newest titles

Happy reading!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Books. Change. Lives.

Copyright © 2018 by Christina Collins

Cover and internal design © 2018 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design and illustrations by Ellen Duda

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Jabberwocky, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Collins, Christina, author.

Title: After zero / Christina Collins.

Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks Jabberwocky, [2018] | Summary: When Elise leaves homeschooling for public school, she copes by speaking as little as possible, but soon her silence becomes an impediment to friendship and to dealing with family secrets.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017045912 | (13 : alk. paper)

Subjects: | CYAC: Selective mutism--Fiction. | Interpersonal relations--Fiction. | Schools--Fiction. | Secrets--Fiction. | Ravens--Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.C64474 Aft 2018 | DDC [Fic]--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045912

Contents

Front Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Back Cover

For mute swans, lone ravens, and “other birds” around the world

AND NOW AS SHE DARED TO OPEN HER MOUTH AND SPEAK…

—Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (translator Margaret Hunt), “The Twelve Brothers”

Chapter 1

It’s amazing how few words a person can get by with.

I scratch a tally mark into my notebook and grin. Yesterday it was two, and three the day before that. Today it’s one. One word all morning: a new record. If Mr. Scroggins hadn’t asked me to name the capital of Russia last period, it could have been zero.

When Miss Looping turns from the board, I move my pencil so it looks like I’m taking notes. I almost feel sorry about not paying attention—Miss Looping isn’t so bad. She wears dark velvet dresses and is in love with Charles Dickens. Her stuffed raven, Beady, keeps looking at me. I sneak glances at his perch, waiting for him to open his beak and kraaa. But he never moves.

Maybe it’s Beady’s stare or Miss Looping’s dresses or her pasty skin that makes people wonder about her. Most students think she’s weird. I don’t mind her. She doesn’t call on me or hold class discussions. Mr. Gankle and Ms. Dively like that sort of thing, so they never give me A’s. Neither does Mrs. Bebeau, who thinks the best way to learn French is to speak it aloud. Miss Looping is the only one who doesn’t penalize me for not talking. She puts A’s on all my papers and jots comments in the margins—things like “good point” and “nice word choice”—and recommends poets I might like. Sometimes I add a note back to her: Thanks for understanding, Miss L. But she never gets the note because you don’t give papers back to teachers after they’re graded.

“Aaaa-choo!”

I jump as Arty Pilger sneezes next to me, spraying my arm.

I hate when people sneeze. Not because of the spraying—well, that too—but because they expect me to say “bless you.” Or “God bless you” if they believe in God.

Someone across the room yells “Gesundheit,” and I relax. My tally remains one.

But lunch is next, and that will be trickier. People like to talk at lunch. I look back at the tally mark in my notebook. If I want my record to last more than three periods, I need a new tactic for the cafeteria today. A stronger shield, harder armor.

When the bell rings, I hurry past Beady, avoiding his gaze. I wish Miss Looping would turn him to face the wall. In the hallway, I empty my books into my locker, all except for one this time. Then I make my way to the cafeteria, armed and ready.

I slip into my seat at the end of Mel’s table. Mel, Sylvia, Nellie, and Theresa are deep in conversation and don’t pause at my arrival. They never do these days. Sometimes their eyes slide sideways, but I don’t always see this because I keep my own eyes down.

I pull The Oxford Book of Sonnets out of my bag, open it, and eat my sandwich. I get through a whole poem without anyone trying to talk to me. Two poems. Two and a half. Why didn’t I think of this before? Read a book—such a simple solution.

“You’re reading at lunch?”

Sylvia’s voice clangs against my armor. I keep my eyes on the page.

“It must be a good book then.”

I force my eyes to move left to right, left to right. If I don’t, they’ll think I heard. They’ll think I’m faking. I can feel them all looking. To these girls, I’m the elephant in the room. And no one can really relax when there’s an elephant in the room, least of all the elephant. I’ve tried sitting at an empty table, but that makes everyone stare more. Like it or not, sitting at Mel’s table is better than sitting alone.

“I’m so jealous of your eyebrows.” Sylvia’s voice again. “I swear they get bigger every day.”

No one responds, so I know her words are meant for me. I try to focus on the typeface in front of me. It blurs. I drag my eyes away in spite of myself and find Sylvia in the seat next to Mel, slowly twirling a french fry between her fingers, a smirk playing on the corner of her lip.

Mel shifts in her seat. “I think they’re pretty.” She must still feel an obligation toward me, considering she’s my neighbor and all—and the closest thing I have to a friend. She’s too late, though. I’m already scanning the other girls’ eyebrows, noting the safe, sure spaces between them—and fighting the urge to reach up and feel mine.

Sylvia’s french fry pauses at Mel’s comment, but only for a split second. Her smirk doesn’t budge. “I could have fixed them for you at Nellie’s sleepover Saturday. Why didn’t you come?”

An open-ended questi

on—Sylvia’s specialty. She sits back and takes a bite of her fry, waiting, watching me. Everyone watches me. Everyone except Mel, who’s examining her food.

I push my tongue against my teeth. One word, any word, and I can start over. I can wipe the slate clean, and they’ll forget I haven’t spoken at this table in the past ten minutes.

Or the past week.

Or the past seven months.

Sweat collects under my arms. I can feel it happening—my throat closing up. The bubble forming. The cop-out coming. Here it comes: My shoulders move up and down in a quick motion. A shrug.

Sylvia cocks her head. “You’re awfully quiet today.”

Today. As if it’s different from any other day.

“Give her a break.” Mel picks up her soda and stirs the straw. The ice crashes together.

Sylvia’s smirk flickers. She shoots Mel a look. “Why? Didn’t her parents teach her how to talk?”

“She talks.”

“When?”

Mel concentrates on her food. I try to catch her eye, but I’m losing her. The longer I go without saying something, the more tired she grows of defending me. One of these days, she might stop altogether.

Hours pass, or maybe seconds, before someone changes the subject to something about the sleepover last Saturday. They always lose interest in the elephant eventually. I can count on that.

I return to the page where I left off.

But my eyes slide upward. Faces look at me funny—funnier than usual. No one else in the cafeteria is reading. The point of the book was to draw attention away from me, to show that I’m busy, unavailable, otherwise engaged. But it’s backfiring. I close the book, pick up my bag, and leave the cafeteria. Mel doesn’t call after me.

I go back to Miss Looping’s room, still empty except for Beady. I’ll have to put up with him staring. At least he won’t talk to me. And if Miss Looping comes back early, she won’t try to make small talk like the other teachers. She’ll let me be.

I sit in the back row near the open window and return to my book. Something moves in the corner of my eye. I look over to Miss Looping’s desk, where Beady is watching me. A fly buzzes past. I swat at it and try to keep reading, but the print blurs worse than before. Instead of poetry, I see Sylvia’s smirk all over the page.

You’re awfully quiet today. You’re awfully quiet today.

My teeth grind. I slam the book shut and punch it with the side of my fist. At the same time, a black shape leaps in my periphery and another noise shakes the room—a shattering of ceramic. I jerk my head up to find Beady on the floor near Miss Looping’s desk, rocking on his side. Miss Looping’s “What the Dickens!” coffee mug lies in pieces next to him.

I grab my book and bolt out the door, my heart thudding.

Relax, I tell myself as I stumble down the hall. He’s a stuffed bird. Top-heavy, that’s all. Top-heavy things tip over sometimes.

Still, there’s something about Beady I’ve never trusted. His feathers are too feather-like, his talons too talon-like. I walk faster, turning left and right under the glare of fluorescent lights, down more halls with burnt-orange walls. Farther ahead now I see double doors and a sign. A word in block letters:

QUIET

I slow, squinting. The word follows me. Haunts me. It won’t leave me alone. I can’t remember when people started using it—there must have been a day, a moment—but it’s all I’ve heard since then.

Elise is so quiet.

Elise, you’ve been quiet. What do you think about such and such?

That’s her over there. The quiet one.

Mr. Scroggins writes the same note on all my social studies papers: Terrific work, Elise. You present a strong, fluid argument. But I wish you’d speak up more in class. You’re very quiet.

I try to ignore the word, but there’s something about it. Something that tells me it isn’t a compliment.

QUIET

Now it appears as illusions on the walls. What next? Voices in my head? Tightening my fists, I walk toward the sign. I’ll break the illusion. I’ll stare it down and scare it away.

The rest of the sign comes into focus.

QUIET

IN THE LIBRARY

The words wink at me. I blink and read them again.

The librarian doesn’t notice me come in. Her back is turned as she arranges books on a shelf. Bernard Billows snoozes at a table in the corner, wearing the same T-shirt and sweatpants he wears every day. I can smell his spoiled-milk cologne from here. No one else is in the library. It must not be a popular lunch spot. I’ve been here only once, seven months ago after the second day of school, back when I was still curious about everything. I’d never seen a public-school library before. But I left after two minutes—there were too many people here then, the jigsaw puzzle club or something.

Green Pasture Middle School loves that club stuff. They have this initiative where every student has to join at least one club or team before spring vacation. The principal keeps reminding us in his intercom announcements. Mel and Sylvia and all of them are in the choir and the drama club. I still haven’t joined anything.

I sit at a table in the farthest corner of the library, near the poetry section, and open my book. It takes me a minute to find my place. Before long, I actually turn a page. And another. No eyes stare at me this time. No one tries to talk to me. I decide to come back for lunch the next day. And maybe even the next.

A bird croaks outside the window, but I refuse to let it break my concentration.

I can already taste the victory of tomorrow’s tally: zero.

Chapter 2

My mother catches me as I sneak past the kitchen. “How was school?”

“Good,” I say. She has no reason to believe this isn’t true. She never gets calls of concern from Green Pasture. Why would she? I’m passing my classes, and the teachers are all too busy keeping the loud kids quiet to worry about the quiet kid. So I keep feeding her the same answer, and she keeps gobbling it up. And it never affects my tally because there’s no counting at home. There’s no need for it. We hardly talk to each other as it is, and when we do, there’s nothing to lose. She’ll still be my mother no matter what comes out of my mouth.

“What do you think?” She holds up the hat she’s knitting at the kitchen table. “Got an order on my website today.”

“It’s nice.” I never criticize her handiwork. Just like I never ask why she doesn’t have a real job in an office building, like Mel’s parents. For as long as I can remember, she’s been working from home, selling—or trying to sell—her knitwear, and teaching online college math. And, up until seven months ago, homeschooling me, if that counts as a job—though she never showed any enthusiasm for it.

She returns to her work now, and I continue on my way.

I stop in the bathroom and lean close to the mirror. Fine hairs cascade from my eyebrows, reaching toward the area above my nose. Almost touching. Almost an M.

I open the cabinet and fumble through my mother’s things: powder, lotion, nail clippers, tweezers. I take out the tweezers, grip a hair, and pull. Nothing happens. I yank harder. A twinge rips through my skin. I shut my eyes. I open them, and my vision is watery. One hair down. It will take forever this way. There must be a quicker method.

I pull back the shower curtain and eye my mother’s razor. I never use her things—she doesn’t like me touching them—but this is an emergency. I wet the razor in the sink and hold it between my eyebrows, sliding it sideways.

I lower the razor. In the mirror, one eyebrow is shorter than the other. Way shorter. My palms sweat. I have to make them even. I can’t go to school like this. I rinse the razor and lift it again.

“What are you… Don’t do that.”

I see my mother in the mirror staring at me. I should have locked the door. She has a quiet way of entering rooms sometimes.

<

br /> She comes forward and rips the razor from my hand. “Why’d you do that?”

“A girl at school said I have a unibrow.”

“That’s ridiculous. You don’t have a unibrow.”

“That’s because I just shaved it.”

“You shouldn’t do that. It’ll grow back thicker and all stubbly.”

“It’s not fair. Your eyebrows are fine.”

“Your father had the Armenian genes. Blame him.”

“Did he have a unibrow too?”

“You don’t have a unibrow.”

“I bet he wouldn’t lie to me.”

My mother’s eyes flash. I’ve seen it before: that glint of loathing. Whether the loathing is for me or my father, or both, I’m not sure. “You think your father never lied? If you’d known him…”

I wait, holding my breath. She never talks about him.

She sets down the razor and grabs an eye pencil from the cabinet. “Here…use this to fill in the shorter one till it grows back. Now can I use the bathroom?”

I stare at the eye pencil. She’s never given me anything of her own before. My stubbornness tells me not to trust it, to refuse this gesture of pity or charity or whatever it is. But in the mirror I see the unevenness again. It does look pretty bad.

“Fine.” I grab the pencil and march past her to my room.

I don’t bother slamming the door. I plop onto my bed and put the eye pencil on my dresser. It’s the only makeup item in my room. I wonder if Mel owns makeup. I’ve never seen her wear any. Sylvia does. Powdery stuff always cakes her pimples, and clumps of mascara cling to her eyelashes. Would it make a difference if I wore any? Can makeup make up for other things, like being “quiet”?

I listen to my mother’s footfalls as I do my homework. Creak, creak, creak to the kitchen. Creak, creak, creak to her bedroom. For someone so good at sneaking up on me, she sure can be loud when she wants to be. Screee. Door opening. Thunk. Closing. She doesn’t call me for dinner, and I don’t check to see if she’s made anything. I work my way through the box of crackers on my desk.

After Zero

After Zero