- Home

- Christina Collins

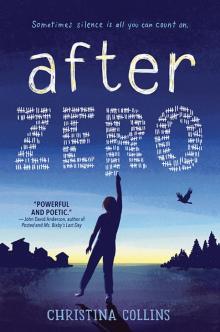

After Zero Page 5

After Zero Read online

Page 5

“Hey, Elise.”

I jump a foot in the air, and my happiness drops to the ground.

“Whoops… Shoot… Sorry.”

I look up, finding myself at eye level with a pair of binoculars.

“I’ll buy you another one.” Conn darts around me to the cash register before I can object with a head shake or a hand gesture. I watch him call the clerk and point to the sticky buns. He takes out his wallet. I could flee while his back is turned—there’s still time. But that would make me a jerk. And I want a sticky bun.

Conn approaches with two paper bags and hands me one. “Sorry about that.”

I smile, which is close enough to a thank-you, and start to turn toward the door, toward safety…

“Are you doing anything right now?”

…but not fast enough. I race to think of an excuse. I could have a test to study for or a dentist appointment or—

“Let’s sit a minute.” He doesn’t wait for me to respond, just strolls over to a table and sits. He bites into his bun and waves at the chair next to him.

I stand there about five seconds and realize I’ve missed my window—the one to two seconds after someone addresses me, in which I need to acknowledge what they said or pretend I didn’t hear. It’s crucial to act within this window. If I hesitate, it’s impossible to pull off the pretending. If I wait too long, it’s awkward. Right now it’s both. I have no choice but to sit.

I join Conn’s table and take a huge bite out of my bun. Does the tally still apply after school? This is new territory. No Green Pasture kids have ever tried to talk to me outside of school—mainly because I tend not to go places where I might encounter them. It doesn’t matter; we’ll be so busy eating that there won’t be a chance to talk. I’ll keep my mouth full the whole time. It’s rude to talk with your mouth full.

“You never came back from the bathroom the other day,” Conn says with his mouth full. So much for that. “Fin scare you off?”

I shake my head and keep chewing.

“There’s this new bird documentary playing at the cinema tomorrow night. It sounds interesting.”

A bird documentary? Not that there are many “interesting” things to do in this town, but a documentary wouldn’t have been my first thought.

“I thought I might check it out. If you want to come.”

I chew as slowly as possible. I’m running out of bites. The bread is dissolving on my tongue, and soon I’m going to have to swallow.

He clears his throat. “We could get pizza after. I heard that place on Main Street is good.”

I guess he hasn’t been at Green Pasture long enough. He still doesn’t know about me. We don’t have any classes together, so he doesn’t realize I’m the last person he should associate with, after Bernard Billows. The feeling I had in Ms. Standish’s office comes flooding back: a blank slate. No preconceptions. No adjective attached to me.

It tempts me.

“I know tomorrow’s Saturday, so you probably have plans.”

My throat sucks the last bits down. My mouth empties.

You’re not going to sit at home on a Saturday night, are you?

I look down at my bun. Maybe it wouldn’t so bad to go see a film and have pizza. I do like pizza.

“No,” I hear myself say.

Conn frowns a little.

“No plans,” I mumble.

“Oh.” He smiles hesitantly. “Cool.”

I’m not sure if I just agreed to go tomorrow or not. I don’t think he’s sure either.

“Why are you wearing those?” I blurt out. The question comes out sharper than I meant, though I didn’t mean for it to come out at all. I need to keep my mouth shut if I know what’s good for me.

“Wearing what?”

I point at his binoculars.

He shrugs. “Why not?”

I raise an eyebrow.

“What can I say? I’m a man of mystery.”

“And alliteration.” Oops.

He raises an eyebrow back at me. “What are you, a poet or something?”

I bite into my bun to stop a smile. Maybe this isn’t so hard. We’re having a conversation. Like it used to be with Mel. Maybe I could ask him if he likes poetry, or what his favorite ice cream flavor is, or if he thinks it’s possible for an inanimate object to fly out a window…

“Yo, Connie boy.”

We look up. Two girls have come into the shop. I recognize Fin right away. I identify the other girl as they approach. I don’t know her name, but she’s a seventh grader like Fin and Mel, and she’s on the track team—one of the hurdlers. I’ve seen her in the girls’ bathroom a couple of times too. She’s someone who would know enough about me. Someone who would have an adjective attached to me.

Conn nods at Fin. “Look who the cat dragged in.”

“We saw you in the window.”

“That’s not creepy at all. You remember Elise, right?”

“You think my memory’s that bad?” She waves a hand at the girl trailing her. “This is Dawn. We have some classes together.”

Dawn raises her hand to the level of her hips and twitches it in a lazy wave.

“Want to join us?” Conn says.

“Sure.”

Fin and Dawn each pull up a chair. I take another bite of my sticky bun, but it’s lost some of its flavor.

Fin plops down in her chair and eyes Conn’s bun. “That’s making my mouth water.” She holds out a hand. “Let me have a bite, Connie boy.”

“No way.” Conn shields the bun from her. “And stop calling me that.”

“You suck at sharing.”

“How unfortunate.” He wolfs down the rest of the bun. “At least we don’t share a room anymore.”

Fin shudders. “Those days will haunt me forever.”

“I know how that is.” Dawn grunts. “My sister farts around the clock.”

“Sounds like someone I know,” Conn says behind his hand.

Fin throws a balled-up napkin at him. The three of them laugh.

I pick at my sticky bun. I feel it happening again. My body turning to stone. My throat closing up. The bubble forming, or the membrane, or whatever it is.

There were so many topics they could have picked. Soccer. Spaceships. Siamese cats. If they’d chosen anything else, I could have found something to say. But siblings? I know nothing about them. I’m the only one at this table who doesn’t have any. How am I supposed to think of something to say? I should have left when I had the chance. I could have lived without the sticky bun.

Fin, Conn, and Dawn are now debating who’s worst off: the youngest, the oldest, or the middle child.

“Definitely the oldest.” Dawn points a thumb at her chest.

“I don’t know,” Conn says. “At our house, the oldest gets the basement to himself. With his own private entrance.”

“Really?”

“That’s because Dónal’s a suck-up.” Fin snorts. “Mom and Dad don’t see his devil horns.”

How long have I been sitting here? Conn glances at me. I know that look. It’s the same look Mel gave me at lunch during those first days of school. It was my inconsistency that confused her then. It’s my inconsistency that’s confusing Conn now. I should have said something right away, as soon as the others sat down. Maybe I still can. Maybe it’s not too late.

But the bubble thickens with each passing second—my own personal snow globe. If someone were to pick it up and shake it, all the snow and glitter would move, but not me. I’m the figurine frozen in the midst of it all. I’m starting to think Sakya Pandita got things backward. If the talkative parrot is shut up in a cage—if birds without speech are supposed to be free—then why do I feel like the trapped one right now?

“He can’t be as evil as my sister.” Dawn flicks her hair.

“Wanna bet?” Fin pulls a dollar out of her pocket.

“Save your money, Dawn.” Conn shakes his head. “You’ll lose.”

The businesswoman stands at the cash register buying something in a cake-sized box. My eyes fall to the doll cake in the display case. Barbie is watching me. I know what she wants to tell me. Say something. Open your mouth. But like me, she can’t talk. Unlike me, she has a legitimate excuse.

I never thought I’d envy a doll.

Say something. Open your mouth.

But it’s too hard. The bubble is too thick, too strong.

Besides, I’m safe here in my bubble. Why should I have to pop it anyway? Why should I have to prove myself to anyone? Why should I have to compete with all the noise? There’s freedom of speech, so there should be freedom of no speech. What’s that phrase cops use when they’re making an arrest? You have the right to remain silent.

I have the right to remain silent.

I feel Fin and Dawn looking at me sideways now, an awareness growing. An awareness that it’s been ten minutes, and one person at the table hasn’t said anything.

Suddenly, the most important thing is to leave, to get out.

As Fin and Dawn go to the counter to order milk shakes, still debating, Conn leans in. “Everything okay?”

I nod, too quickly. “Just tired. Didn’t sleep last night.” Of course now the bubble pops. Go figure.

“Shoot. Wouldn’t have kept you if I’d known.”

I think he buys my excuse. It’s hard to tell. But I know it will only last so long. When I use the same excuse next time, and the time after that, he’ll catch on. Luckily, there won’t be a next time. It was nice while it lasted. He would have found out about me eventually. The blank slate fills in. The adjective attaches. Quiet, quiet, quiet.

I stand.

Conn stands too. “Heading out?”

I nod again.

“All right.” His hands find his pockets.

I almost leave without saying anything. But there’s a crease in his brow and a heaviness in his slouch, as if he’s trying to figure out what he did wrong. I don’t like that I made someone look that way.

“My mom needs help with something.” The lie tumbles out of me. “It’s just us two at home, so…”

Conn’s brow relaxes a little. His shoulders too. “Ah, gotcha. Duty calls.” He jangles the change in his pocket. “Well, then, guess I’ll see you later.”

I’m ready to slip past him and get the heck out of here, but he’s still looking at me. The girls pause in their argument at the counter, looking too.

“Adios,” I squeak. Then I walk—try not to run—out the door.

Adios? I cringe on the curb. Bye or later would have sufficed. Or no word at all. I hurry down the sidewalk, annoyed because my happiness was disrupted. Annoyed because I can’t go to Patsy’s Pastries anymore. Annoyed because really, Conn, Fin, and Dawn did nothing wrong. Annoyed because the truth is, even if they hadn’t been talking about siblings—even if they’d been talking about soccer or spaceships or Siamese cats—I still wouldn’t have said anything.

I take a bite of my half-eaten sticky bun and walk to the bike rack. A man rounds the corner and bumps into me. My last bit of happiness drops to the ground. “Sorry,” the man grumbles, hustling past. I watch the bun roll away and almost laugh. The world can’t let me eat one little sticky bun in peace. The problem, I decide, is other people. Other people taint everything. They bump into you, try to talk to you, interrupt your happiness, knock it to the ground.

I mount my bike and push off, glancing mournfully at my bun’s remains. There’s already a bird pecking at them.

Its feathers are black, almost bluish in the setting sun.

The bird looks up at me.

A car beeps. I realize I swerved out of the bike lane. I stop to regain my balance and look back across the street. The bun is there, but the bird isn’t.

I push off again, cold creeping through me. I whiz down Main Street and turn toward home. I catch myself scanning the sky and the trees. Ravens are common, aren’t they? Like sparrows and squirrels. It couldn’t have been the same one.

It couldn’t have been Beady.

Now I’m even more annoyed because I’m letting a bird get to me. That’s how bad this day—this week—this school year—is going.

Chapter 8

The front door groans as I open it. I glare at the hinges and tiptoe up the stairs.

“How was school?”

I wince. So close.

I turn to find my mother in the living room knitting a scarf. “Good.” The fib rolls off my tongue.

“You’re home late.”

“I joined the track team.”

“Oh? Good for you.” She doesn’t look up from her work. I suppose she doesn’t want to mess up the stitching. I was hoping to keep avoiding her, in case she asks about her door being open. I just need to get by before she has a chance…

“And how are classes?”

“Fine.” I turn toward the hall.

“Everyone being nice?”

My eyes slide back to her. Normally she doesn’t ask this many questions. She must be either really bored or gearing up to ask about the door. “Mmm-hmm,” I say, hoping that will satisfy her.

“Even that girl?”

“What girl?”

Her knitting needles fly, dip, and weave, scooping up loops of yarn. “You know. The one who commented on your eyebrows.”

My jaw locks. Just when I’ve forgotten about that, she has to swoop in and remind me.

“Remember, she’s just jealous.” She knits faster. “Anyone who says things like that is jealous.”

Is this her attempt to say something motherly? Maybe I should give her credit for trying, but that’s the thing: it feels like she’s trying, forcing it, reciting lines from a script. Like she never got the instincts other mothers have. I didn’t notice so much when I was little, but the more time I spent at Mel’s, the more I picked up on all the things her mother does that mine doesn’t do with me. Like make eye contact. Or kiss me on the forehead when I’m going out the door. Or say things like sweetheart and love you. Even Miss Looping calls me honey sometimes, and she’s not anyone’s mother. It’s not that I need my mother to do these things. It’s not that I need her to do anything except, I don’t know…interact with me as though it’s not an obligation. Maybe then it wouldn’t feel like an obligation for me either.

“Right.” I start down the hall.

“Oh, could you make sure your window’s shut?”

“Uh-huh.” I keep walking.

“Don’t want more creatures getting in.”

I pause. “Creatures?”

“Nothing to worry about. I left my window open yesterday, and a bird flew in.”

“A bird?” I look at her over my shoulder.

“Scared the wits out of me.” She half laughs. “I ran outside and drove off. And when I got back, I couldn’t find it. Must have flown back out.”

I squeeze my backpack strap. So that’s why her door was open a crack?

“What kind of bird?” I ask in spite of myself.

“Might’ve been a crow?” She knits a few more stitches and sets down the scarf. “I didn’t get a good look. At least it wasn’t a bat.”

I stare after her as she goes into the kitchen. So I haven’t been imagining him. My mother saw him too. The raven was here at the house.

I’ve heard of people having stalkers, human ones like that boy who had a crush on Mel last year. Mel told me how he’d follow her around school and wait at her locker and keep asking for her phone number. At least that bordered on flattering. But whoever heard of a bird stalker?

And what does he want?

• • •

I turn onto my stomach and slide my hands under my pillow to ke

ep them warm. I hate this time of night. This is when things settle, sink in, suspend. This is when events replay. A glance from Mel in the hall. A grade on a project. A boy with binoculars in Patsy’s Pastries. His words in my head, echoing. Hey, Elise.

I blink in the dark. I wonder if it means anything when someone calls you by name. When they remember your name though they’ve only met you once. Hey, Elise.

It seems…personal.

I can’t stop the tingle of warmth that spreads across my scalp, like the one I feel when Mel brushes—used to brush—my hair, and when I read Miss Looping’s comments on my papers.

And then the other feeling, that stiffening of muscles, that churning or burning or yearning in my stomach, like the one I felt when I used to sit at Mel’s lunch table, and when Fin and Conn and Dawn were joking in the pastry shop.

I want more than anything to fall asleep.

I grab my earbuds and jam them deep in my ears, turn on the music, and raise the volume as high as it will go.

But I still hear words echoing.

Hey, Elise. Hey, Elise.

My throat scratches. I get out of bed and tiptoe down the hall past my mother’s closed door. In the kitchen, the digital clock on the microwave says 3:01 a.m. At least I don’t have to get up for school in the morning. I open the fridge, its blast of light blinding in the dark. I chug orange juice from the carton. When I finish, I notice the expiration date has passed. My mother never misses something like that. Is she testing me to see if I’ll throw it away?

I put the carton back in the fridge and close the door. I sigh and open it again. What’s the point in keeping expired juice around just to prove a point? I take the carton over to the sink to dump it out.

Something flashes past the kitchen window.

I put down the orange juice and lean over the sink, looking out and trying to spot my stalker.

A weak glow in the shed’s window draws my eyes.

Expired orange juice gurgles in my stomach. And something comes back to me. A figure in the night, out there by the shed. I thought it had been a trick of the light or the unsleep. Had I seen someone?

The light flickers. Movement.

I duck to the floor as thoughts fly through my head, each crazier than the one before: A fugitive is camping out in there, hiding from the law. Or a serial killer, planning an attack. Or a werewolf, lying low until a full moon.

After Zero

After Zero