- Home

- Christina Collins

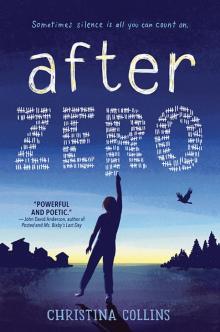

After Zero Page 6

After Zero Read online

Page 6

Before my thoughts can spiral further, I crawl across the kitchen floor. Once I reach the hall, I get to my feet and hurry to my mother’s door. For the first time since I was maybe five, I knock.

No answer. I knock again. Is she ignoring me? I knock a third time. My heart bangs in my chest. What if the trespasser outside can hear me knocking? I twist the knob. It’s not locked. I push the door open. I don’t care if it’s the middle of the night; I don’t care if she doesn’t want me going in her room. This is an emergency. We need to call the police.

I flip on the light and stare at my mother’s bed: empty, unmade, the covers flung down.

• • •

I watch the shed through the gap in my curtains, not daring to part them more than an inch.

The patch of light in the window blinks out. I suck in my breath.

The moonlight catches on a shape coming out of the shed door: a slight hunch, wisps of hair, the bulk of a nightgown.

The orange juice swishes again in my stomach. I watch my mother’s silvery outline close the door, lingering a moment. Then she turns back toward the house, disappearing into shadow.

I jump onto my bed and lie flat on my back, listening.

A minute later, there’s a creak in the hall. The slightest click of her bedroom door. The back entrance to the house is a sliding door, so it doesn’t groan like the front door, and I’m sure it wouldn’t make a sound if someone slid it very, very slowly, which is no doubt what my mother just did. That explains why I didn’t hear her come in last time either.

I lie this way for a while, waiting.

The silence continues.

I climb out of bed and change into jeans, a jacket, and sneakers. Grabbing a flashlight from my closet, I tiptoe to the back door. I slide it open the way my mother would have—very, very slowly—and trek through the overgrowth toward the shed. The woods push against the fence, as if they’re leaning to see who goes there. I shiver but keep walking.

When I reach the shed, I shine the flashlight in the little side window, illuminating the filth on the glass and the rusty shovels and rakes leaning against it, blocking whatever lies beyond it. More of the same, I always assumed. But what would my mother want with past residents’ yard tools in the middle of the night?

I go around to the shed door and shine the light on the latch. I try to slide the bolt, but the rust on the metal causes so much friction that I have to jerk it little by little until, without warning, it jerks all the way out and scrapes my knuckles against the wood of the door.

I rub my hands and wipe the rust off, staring at the door. I take a step back. What if there are dead bodies in there? Or a secret laboratory, or—

No. I didn’t get dressed and come all the way out here and scrape my knuckles just to chicken out. Just to go back to bed and lie wide awake wondering. Even if I might not like what I’ll find, I’d rather know.

I breathe in and push open the door.

The beam of my flashlight reveals small cardboard boxes and a battery-powered lantern. I turn the lantern on. It flickers once before shedding a dim glow—the glow I must have seen from my bedroom window. I look around. Other than the rakes and shovels leaning against the window, there are just half a dozen boxes. That’s it. Not that I wanted to find dead bodies or a secret laboratory…but I can’t help feeling underwhelmed. Then again, when has my mother ever been interesting?

I move to the nearest box and lift the flaps. A pacifier, baby shoes, a checkered bib. I pull out a worn envelope packed with photographs. In the first picture, a baby crawls on a carpet, smiling, reaching toward the camera, with big eyebrows and a curlicue of dark hair. I stare. Is that me? I didn’t think my mother had any pictures of me.

I leaf through more. Another of the baby, this time in a sandbox.

Then there are two in the sandbox, one a baby, the other a toddler.

Then they’re at a playground together. Then they’re on Santa’s lap. Then they’re squinting in front of some church, dressed in little suits and ties.

Boys. They’re both boys, with eyebrows that almost meet in the middle.

In another picture, the boys sit on a park bench. The older boy is blowing bubbles through a bubble wand. The smaller boy hugs a teddy bear wearing a bow tie. He looks like he’s about to cry.

I turn the picture over. Someone has jotted in slanting letters: Eustace age 2, Emerson age 4. The handwriting looks like my mother’s.

In the next photograph, the boys aren’t alone. The two of them stand on either side of a dark-haired pregnant woman. Behind them, a tall mustached man grins over their heads, raising a beer bottle to the camera. The woman beams down at the boys as they lean in kissing her baby bump. She’s slimmer than my mother—except for the belly—and younger. But her face is unmistakable.

If I were to guess what my mother looked like ten or fifteen years ago, this would be it.

I turn the picture over, and for once there’s a date: seven days before I was born. And a caption in that same slanting hand, with a smiley face drawn next to it: E & E kissing their sis.

I drop the photograph on the floor as if it seared my fingers. The caption stares back at me. That word, sis. I push the first box aside, finding other boxes behind it, labeled with names in black marker. Emerson, one says. Eustace, says another. I pull open the flaps of a box labeled Emerson. Inside there’s a heap of stuff: Hot Wheels. Building blocks. A fraying Batman blanket. I move to a box labeled Eustace. A rubber ducky. A picture book about a tap-dancing turtle. A teddy bear wearing a bow tie—just like the one in the photograph.

My chest tightens as I run my fingers over the bear’s fur, the worn spots, the places where someone squeezed him too many times.

“Don’t touch that.”

I jump and look up. My mother stands in the shed’s doorway, her knuckles white.

Chapter 9

It’s odd seeing her in her nightgown. In the mornings, she’s already dressed when I leave for school. After dinner, we go to our rooms and shut our doors. But seeing her out here in the middle of the night, her graying hair a mess, purple bags underscoring her eyes, makes me think I have two mothers I don’t know instead of one. She’s only a few feet from me, but she seems farther, like at the movies when you see and hear the actors, but if you were to try to touch them, all you’d feel is the movie screen.

“Put it back.” My mother’s glower fixes on the teddy bear. “You shouldn’t be in here.”

Her words barely reach me through the fog in my head. “What is all this?” I blink at the teddy bear, at the other toys, at the pictures fanned out on the floor. “Whose stuff is this?”

My mother makes a show of rubbing her eyes. “I’m too tired for this right now. Just go to your room.” She steps inside, away from the doorway, so I can get by.

I stay where I am and hold up the photograph of the boys kissing the pregnant woman’s belly. It shakes because my hand shakes. “Who are these people?”

She glances at the photograph. Her fingers twitch at her sides, as if itching for something to knit, for an excuse to not meet my eyes.

“Is this you?” I point to the pregnant woman in the photograph.

“I said go to your room.”

“Is it?”

She doesn’t say no. Why doesn’t she just say no?

Something about the lighting in here dizzies me. It was all a trick—the high grass around the shed, and the tools at the window, rusting like the door latch… They were all meant to add to the illusion, to make me believe there was nothing but rubble and spiderwebs in here.

I push away the photograph. “This is messed up.”

“Excuse me?”

I gesture at the boxes, the toys, the pictures. “This is all crazy.” My words rush out in a croak-laugh. “Some crazy joke.”

“You think I’m crazy?” There’s that flash

in her eyes, one I’ve seen before.

I don’t move. I half expect her to grab me, to drag me from the shed, to throw me over the fence and into the woods. To discard me like she’s always wanted to. This is her chance. I brace myself.

“You shouldn’t have said that,” she hisses through her teeth. “You shouldn’t say things when you don’t even know what you’re talking about. You have no idea what I’ve been through with your brothers and—” She presses her lips together.

“Brothers?” I stiffen.

She winces and closes her eyes.

“I don’t have any brothers.” My words sound far off, as if someone is talking outside.

“Are you happy now?” she murmurs. “You wanted to know who it all belongs to.”

“I don’t have any brothers.”

Her eyes open, shiny now, and find mine through the movie screen. “You think I haven’t wanted to tell you? If you’d had the decency not to snoop around, you would have found out the right way. At the right time…” She balls up her fists and looks around at all the boxes. Her eyes seem to strain, as if seeing other things. “Go ahead, call me a bad mother. Everyone else did. No one understood why I couldn’t keep them here. No one except…” A sound erupts somewhere in her throat, an ugly gurgle. Then she’s turning, running through the doorway and across the backyard, disappearing around the side of the house.

I clutch my stomach, listening. I hear the station wagon start and the wheels roll off down the gravel, down the hill, into the night—or more like the morning.

No one understood why I couldn’t keep them here. What did she mean?

I turn and tear through the rest of the boxes. An Etch A Sketch, a Mr. Potato Head, a kaleidoscope. More toys that weren’t mine. Used coloring books, stationery, cards. No birthday cards this time, but cards with phrases like Thinking of You or With Sympathy on the front. I glance inside some of them. Vague notes addressed to my mother have been scribbled to personalize printed verses.

Deepest sympathies and healing prayers.

Very sorry to hear about the accident.

Devastated to learn what happened yesterday.

I linger on the last card’s date: April 14th. I was born on the thirteenth.

Sweat spreads across my forehead and the back of my neck. I force myself to look inside the other cards.

Hang in there, hon. God’s testing your faith.

To think they were minutes from you and the baby… I’m so sorry.

Condolences for your loss—praying your sons will pull through.

I sit back on my haunches. The accident…your loss… I knew a drunk driver had killed my father when I was a baby. My mother had told me that much. But I didn’t know it had happened the day I was born. A feeling overwhelms me, bulging in the center of my gut: It happened because of me. My father was driving to see me at the hospital or wherever I was. And it sounds like he wasn’t alone in the car. The sweat on my neck trickles down my back.

The boys… What became of the boys? My…brothers?

The phrase rings strange in my head. My brothers. Did they “pull through”?

I dig for more cards, more clues. I search every box in the room again, throwing contents over my shoulder. But I find nothing else, nothing to answer the rest of my questions, to settle the dread and orange juice squirming in my belly.

And my mother has left me here by myself.

I try to think through the fog of the unsleep. She said belongs. The stuff belongs to my brothers. Present tense, not past. She wouldn’t have said that if they hadn’t “pulled through,” would she?

I push away the papers and close my eyes. My head hurts from straining to make sense of things. What I wouldn’t give, suddenly, for it to be yesterday, when all I had to worry about was my tally and where to go during lunch. What I wouldn’t give to be in the cafeteria contemplating how to avoid one of Sylvia’s open-ended questions.

At some point, seconds or minutes later, something clamors behind me. I jump and turn. One of the rakes is on the floor; it must have slipped. The sound rouses my muscles back to life, pushing me out the door, into the house, and up the stairs to my bedroom. I dump schoolbooks and papers out of my backpack and repack it with things within reach—socks, jeans, T-shirts, a sweatshirt. I pick up my notebook, the one with my tallies, and finger its worn edges, its familiar spirals. I slip it in my bag too, and then force a comb through my tangles before sticking in barrettes to keep my hair out of my face. I haven’t slept in ages, but my thoughts couldn’t be clearer. I know what I have to do. I lift my pillow and grab the birthday card from Granny P, eyeing the return address in the top left corner of the envelope—the zip code that’s two numbers off from mine. If my mother won’t tell me anything, I’ll get answers from someone else.

I slip the card in my backpack. Then I pass through the kitchen, filling a thermos with water and grabbing a box of crackers before heading out the front door.

• • •

For the first time in seven months, I’m on Mel’s front steps. I’m not sure what time it is. The air is cool, but the sun is up, and I can hear the clang of pots and pans from the kitchen window. I lean my bike against the railing and ring the doorbell. My knees shake. I tell myself it’s because of the bike ride.

As I wait, a shape hovers in the corner of my eye—something sitting on the fencepost. I turn in time to see a jet-black bird flying away, but right now I don’t have the energy to care.

Mrs. Asimakos answers the door in her bathrobe. “Oh. Elise.” She smiles. “Haven’t seen you in a while.”

Somehow I manage to smile back.

“We’ve missed you around here. Would you like some pancakes? I’m about to make a batch.”

“No, thank you. I…was wondering if I could print something.” I was always able to talk to Mrs. Asimakos, at least here at the house. But it’s been seven months since I’ve spoken to her, so my words come out a little wobbly. Or maybe that’s the unsleep.

“Of course. Come on in.”

I step into the foyer. It still smells of pinewood. I look around at the familiar relics: the coatrack, the umbrella stand, the shoe mat. The half-moon table with framed pictures of Mel and her sister. Beyond that is the doorway to the living room, where Mel and I used to tinker with her father’s old camcorder and make “movies,” which weren’t really movies but bad attempts to keep our faces straight while reciting soap-opera lines we’d made up seconds earlier. We always made a fuss of watching each video after.

“Ew, I look like a fish!” Mel would squeal and cover her eyes.

“Ew, my arms are so awkward!” I’d chime in.

Then we’d reassure each other that no one looked fishy or awkward, and we’d keel over laughing at everything our screen personas said and did. Each “movie” was a blooper reel more than anything else.

It’s funny to think of those videos now. If I were to watch one, would I recognize the person next to Mel? I think I would envy her, a girl who still thinks she can be a movie star. A girl who’s still friends with Mel. A girl who hasn’t gone to Green Pasture yet. Or started a tally yet.

Or seen what’s in the shed yet.

Mrs. Asimakos leads me to the computer in the study room. “I’ll go see if Mel’s up.”

“Thanks.”

I sit in the desk chair and pull out the envelope with Granny P’s return address. Glen Forest Cottage, North Commons, Scavendish. No street number—that’s odd. Maybe she lives in some kind of retirement community. That is, if she still lives there. I look at the card again. I heard somebody’s turning four… She sent this when I was four, close to nine years ago. I chew the inside of my cheek. A lot can change in nine years. She could have moved. She could be anywhere in the country, the world. I don’t even know her real name. She wrote Granny P on the envelope and the card. And if somehow she still lives at this addr

ess, who’s to say she’ll know or remember anything about my brothers? Who’s to say she’s still “with it”? She must be pretty old by now.

She might not even be alive anymore.

But I have to at least try. As long as there’s a chance, even a slim one, I have to give it a go.

I type the return address into the computer and look up directions. Google locates North Commons, but not the cottage itself. It’s thirty-five minutes north by car. Two hours by bike. Five and a half hours by foot. I click Print.

As the printer whirs, I close my eyes and breathe in. The comfort of Mel’s house makes me want to curl up on the soft, clean carpet and let the Asimakoses’ cats sniff me all over. I restrain myself. I probably shouldn’t be here in the first place. I could have printed directions somewhere else—tried the town library when it opens. But if I could just talk to Mel, tell her about the boxes, the photos, the run-in with my mother, the sympathy cards…she’ll overlook my inconsistency this time. I know she’s still my friend. I know she’ll help me. She’ll know what to do, or at least what to say.

Maybe she’ll even come with me.

Voices rumble from the kitchen. I grab the directions and move toward the voices and the smell of pancakes.

“Why’s she here? It’s seven thirty in the morning. On a Saturday.”

“She said she needs to print something.”

“Well, tell her I’m not home.”

I pause halfway down the hall.

“I already told her you’re here.”

“Tell her I’m sick then.”

“Mel, honey, what’s going on with you two?”

“Nothing. She’s just…gotten weird since school started.”

“Weird how?”

“I don’t know. She acts rude, like no one’s good enough to talk to. Even me. Tell her I’m sick, okay?”

I hear a sigh and footsteps. I back away down the hall. In seconds I’m out the door, mounting my bike, pedaling back up the hill. I don’t look back.

After Zero

After Zero